The blueprint for success includes a mix of tools and programs that bring teams together.

When patients arrive at HCA Healthcare’s Alaska Regional Hospital in Anchorage, whether for trauma, planned surgery or rehabilitation, their immediate medical diagnosis is the priority. But where they’re coming from — and where they’ll be returning to after discharge — can be just as important to their long-term recovery.

Due to the sheer vastness of The Last Frontier, with its soaring mountain ranges and endless stretches of tundra, the 49th state and its remarkably diverse population, including its Indigenous people, create a unique healthcare environment for the colleagues of Alaska Regional.

“Our team puts a great deal of effort into recognizing and addressing the unique challenges posed by Alaska’s geography, harsh environmental conditions and limited resources that some of our patients may face once they return home,” says Alaska Regional CEO Jennifer Opsut. “Providing culturally competent healthcare that respects traditional practices and values is essential, and I’m extremely proud of the part our team plays in respecting and honoring this diverse population and delivering culturally competent, patient-centered care to Alaskans from all over our great state.”

Many of Alaska Regional’s Indigenous rehabilitation patients have traveled hundreds of miles to receive care in Anchorage. Alaska Regional’s proximity to Merrill Field airport makes it a destination for emergency patients — such as stroke patients or people injured in accidents — who need to be flown into the city.

Providing culturally competent healthcare that respects traditional practices and values is essential, and I’m extremely proud of the part our team plays in respecting and honoring this diverse population and delivering culturally competent, patient-centered care to Alaskans from all over our great state.— Jennifer Opsut, CEO, Alaska Regional Hospital

Serving rural communities

“We generally define a rural patient as someone who needs to access their home and doesn’t have a road system to do so,” says Ellen Lechtenberger, RN, CRRN, Alaska Regional’s director of Rehabilitation Services. “However, rural can also be categorized from a healthcare perspective as someone who doesn’t have access to service providers such as home health, outpatient therapies or other aspects of the healthcare system that might be needed based on their particular condition.”

Chief among the challenges of serving rural patients is that preventive healthcare is not always easily achieved in remote areas. “A lot of our patients never got connected to a health system to begin with,” says Ellen. “So if we were to just send them home, they would be unconnected and unable to access care.”

The main hospital serving the Alaska Native population is the Alaska Native Medical Center, or ANMC, a nonprofit secondary and tertiary care facility in Anchorage that is the hub of healthcare for Alaska Natives and other Native Americans, providing medical services to more than 150,000 patients annually.

Remote villages may only have a village health aide, and that individual may have minimal training, if the location has any medical professionals at all. Because HCA Healthcare doesn’t offer any direct outpatient care, the rehabilitation staff and case managers must develop a knowledge of each patient’s living conditions in order to provide and coordinate proper care.

“We give that family and patient a bit more guidance about what to do,” says Ellen. “It’s more of our awareness of what they don’t have and how can we remediate that in the two weeks we have with them.”

Understanding every patient who walks through the door starts with understanding where they’re coming from. There can be a lot of information gathering when first working with patients from rural or remote areas. Does the patient have indoor plumbing, or do they use an outhouse? Do they need to be towed in on a sled behind a snow machine? If the patient is self-subsisting, can they safely return to hunting, fishing and driving a snow machine?

Our goal in rehab is to teach the individual to be as independent with their own function as possible, because we know that this is best for their long-term health [and] recovery, and in order to prevent them from having health regressions.— Ellen Lechtenberger, RN, CRRN, director of Rehabilitation Services, Alaska Regional Hospital

Understanding opportunities and challenges

Alaska Regional’s point person for coordinating recovery plans with ANMC and other healthcare and transportation entities is case manager Amy Lynch, RN.

“When I do my initial case management, discharge planning or assessment with the patient and the family face-to-face, these are all questions that we go through,” says Amy. “What’s your living situation? How can you get there? Do you get there by car, boat, snow machine or four-wheeler? Do you have bathroom facilities, or is it a group bathroom?”

The hospital’s rigorous inpatient rehabilitation program is tailored for patients needing two or three therapy disciplines, including speech, occupational and physical therapy. Patients receive a minimum of three hours of therapy, five days a week. The average length of stay is 14 days, after which the patient is either transferred to a skilled nursing facility or an assisted living facility, or returns home.

“The first way we assist our patient is by having an awareness of their lifestyle and by ensuring the plan of care is formulated based on the reality of their situation,” says Ellen.

From left, Amy Lynch, RN, case manager, and Ellen Lechtenberger (right), RN, CRRN, Alaska Regional’s director of Rehabilitation Services.

Patients who return home are provided a binder detailing their exercises and other rehabilitation routines. That information can be used as a blueprint for continued recovery.

The planning process also incorporates coordinating medical needs, often with ANMC, and the complex role of transportation to ensure that patients, their medical equipment and their aides all arrive at roughly the same time.

“For rural Alaskans, we rely 100% on local airlines and very small aircraft for transportation of our patients to outlying areas,” says Amy. “There is no car or boat that can get a patient to Savoonga (680 miles from Anchorage) or Bethel (398 miles).”

“It’s common for rural Alaskans to utilize a four-wheeler or snow machine to get to their home in the smaller outlying villages,” she says.

There are also a number of cultural realities that the rehabilitation staff and case managers encounter. With more than 20 dialects associated with the Indigenous populations of Alaska, there can often be a language barrier.

Cultural differences can also inform how the care provider and care recipient perceive their goals.

“Our goal in rehab is to teach the individual to be as independent with their own function as possible, because we know that this is best for their long-term health [and] recovery, and in order to prevent them from having health regressions,” says Ellen.

The family-centric values of many cultures can often result in a communal approach to healthcare. Caregivers have seen the benefits of communities who care for their families as an act of service.

“Each person relies on the others’ skills, and the wealth is shared by the community,” says Ellen. “Therefore, if someone has a stroke, they can still be fed, housed and cared for.”

“We have to determine with the patient and family what the goal is for them and plan our care based on their goals while ensuring that they understand the rationale behind our goal to allow the person to be as independent as possible,” she explains. “For example, feeding their loved one can constitute honor and respect, but feeding someone may actually impair their ability to recover the function of their arm after a stroke.”

Further, the Alaska Regional staff connects patients and families with telemedicine therapy providers when those services are available. “We utilize telemedicine to provide remote training sessions to caregivers,” says Ellen. “Our therapists have created safe simulations of hunting, fishing and berry picking to help the patient feel that the therapeutic activities they are performing have meaning in terms of their real-life needs.”

Meeting the needs that matter most

The need for these services can’t be understated. According to Ellen, Alaska Regional cared for almost 250 rehabilitation patients (roughly 17% from Indigenous populations) in the 12 months prior to early September.

Being a facility that patients can trust in and rely on is a privilege and a necessity. Faced with some of the harshest conditions and most remote communities, serving Alaska’s patients also has its rewards. “I love watching the progression of the patients. That’s what’s rewarding to me,” says Amy.

Ellen, who has worked on Alaska Regional’s inpatient rehabilitation unit for 18 years, has seen over and over again the importance of empathy and open-mindedness at the bedside.

To help a person through the grieving process while simultaneously teaching them to do things they don’t believe they can do or don’t want to do is very powerful. You have to be able to create a rapport fast, build trust fast and teach endlessly.— Ellen Lechtenberger, RN, CRRN, director of Rehabilitation Services, Alaska Regional Hospital

Caring Collectively

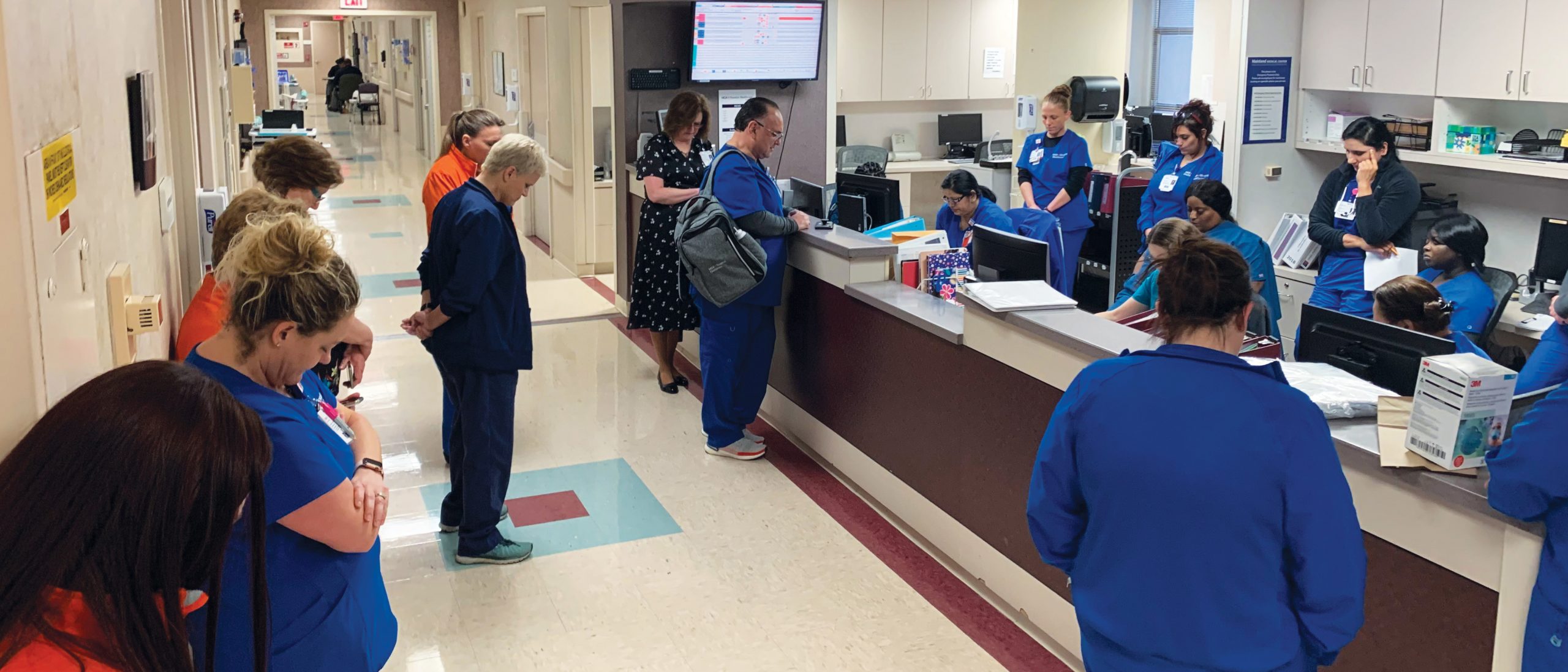

Given the complexities of serving a population as wide-ranging as rural, remote Alaska, the rehabilitation staff of Alaska Regional Hospital needed to ensure that all caregivers were on the same page regarding each patient. The answer, says Ellen Lechtenberger, RN, CRRN, director of Rehabilitation Services, was a multidisciplinary approach.

To address inefficiencies, the rehabilitation team and physicians decided roughly two years ago to implement multidisciplinary rounding with each other, where the care team gathers together five days a week to discuss needs and care plans.

Coming together as a team in this way has produced exceptional results, even with a population that includes stroke patients who are going home to very remote locations.

Patient satisfaction is currently at the 92nd percentile.

“Our operations are excellent because we come together,” says Ellen.

The Magnitude of Our Medical Reach

Quality healthcare is available to our patients across the globe. From Alaska Regional to HCA Florida Mercy Hospital more than 4,900 miles to the south, and across the Atlantic to our hospitals in England, HCA Healthcare exists where patients and people need us.

Bonding Over the Iditarod

The legendary Iditarod sled dog race, held annually, runs from Anchorage to Nome, celebrating the Great Race of Mercy. In 1925, a diphtheria epidemic threatened Nome. The outpost’s antitoxin supply had expired, and the nearest replacement serum was in Anchorage, nearly 1,000 miles away. Once a route was determined, a 20-pound cylinder of serum was sent by train 300 miles from the port of Seward to Nenana.

Matt Paveglio (left), a registered nurse and sled dog racer, competes in the Iditarod sled dog race — a bonding moment for patient Lauren Guice (right).

Just before midnight on Jan. 27, the serum was passed to the first of 20 mushers and more than 100 dogs who relayed the lifesaving package 674 miles to Nome. The dogs ran an average of 31 miles each, with musher Leonhard Seppala and his dog team, led by the incomparable Togo, covering 261 miles of the route’s most treacherous terrain. Musher Gunnar Kaasen and his team, led by the famous Balto, arrived in Nome on Feb. 2 with the serum.

Almost 100 years later, 10-year-old Lauren Guice found herself in her own race against time. In 2020, Lauren arrived at Alaska Regional Hospital’s emergency room suffering with a fever and severe abdominal pains. She and her parents soon learned her diagnosis — stage 4 metastatic germ cell ovarian cancer.

In the ER, Lauren met Matt Paveglio, a registered nurse and sled dog racer who would go on to compete in the 2022 Iditarod. The two bonded over their love of canines, and Matt used their conversations about sled dog racing and the importance of teamwork to keep Lauren calm as he prepared his young patient for the X-rays and CT scan that would reveal her cancer.

Matt kept in touch after Lauren was transferred to a children’s hospital. When she later underwent chemotherapy, he collected 50 stuffed huskies from throughout the United States for her.

“It was her very own Iditarod team,” says Lauren’s mother, Erica Guice. “Matt told Lauren which one was the pack leader. Her name is Nya, and she sits on Lauren’s dresser even today.”

In 2021, Matt’s mother, Dee, received the same diagnosis of ovarian cancer and passed away in August. To commemorate his mother, Matt named his 2022 Iditarod team DEEtermined, and he competed in his first-ever Iditarod in honor of Lauren and her journey. During the race, he delivered hygiene kits to local villages.

That year, Lauren, 12, was ruled cancer-free, and she’s now waiting to be formally considered in remission when she turns 15. Throughout her ordeal, she drew inspiration from the Iditarod.

“She kept saying, ‘We are almost to Nome,’” says Erica. “Just like the Iditarod, just like the dogs, we’re almost to Nome.”