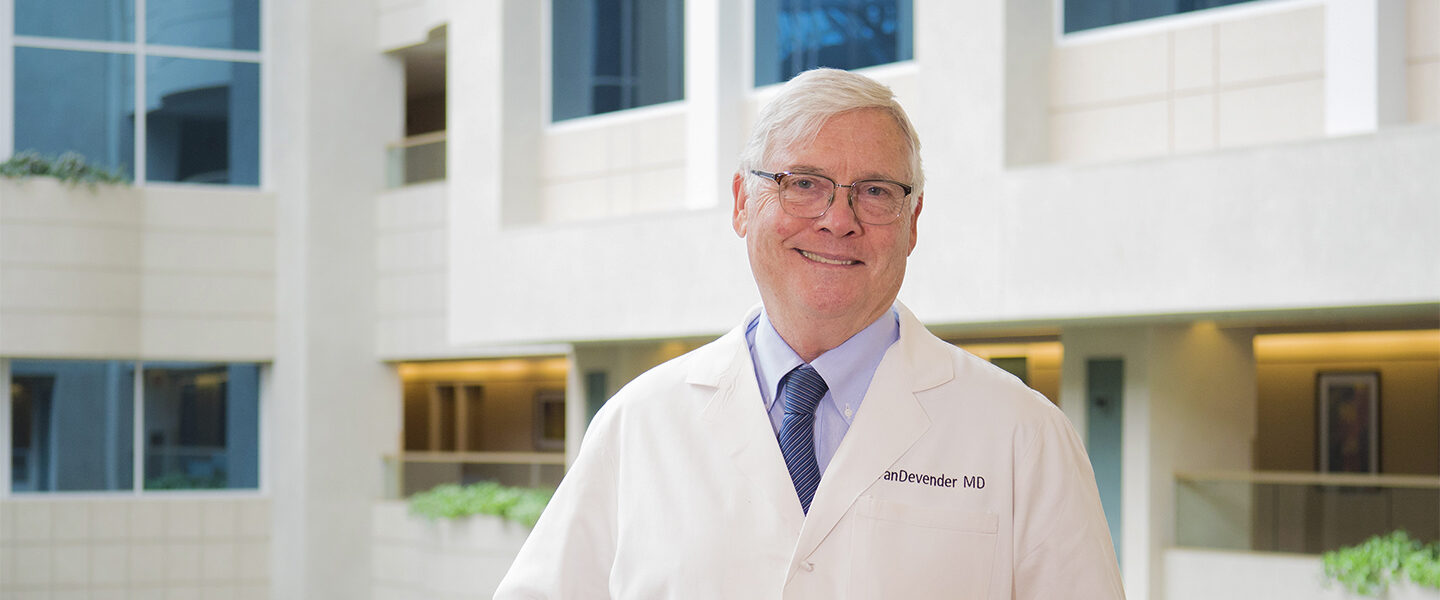

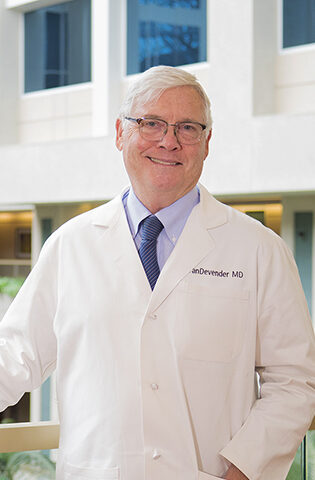

One of HCA Healthcare’s most iconic figures reflects on four decades of practicing medicine.

Dr. VanDevender, a graduate of The University of the South in Sewanee, Tennessee, earned his master’s degree in philosophy and theology from the University of Oxford in England before receiving his M.D. from the University of Mississippi. Next year will be his 40th year of private practice in Nashville.

Dr. VanDevender ultimately chose medicine, but he maintains that there’s a definite spiritual side to his calling. Recently, he sat down with us to reflect on his storied career.

Q: What is the most important aspect of medicine?

A: Touch — human contact — with the patient is so vital, but we can’t see everyone as often as we’d like. When I started in private practice in 1982, my first day was with my partner, Dr. Thomas Frist, Sr., the co-founder of HCA Healthcare. Dr. Frist was a real, wonderful, honest-to-goodness doctor. We went to see my first patient, and he said, “Let’s think more about the care of the patient, not the treatment. I’d like to share with you four things that I have taken with me to the bedside and to the clinic every day.”

Q: What were those four things?

A: The first is the idea of dignity — of all people. Dignity and respect are very different. Respect is something you earn; dignity is something you have. Getting to know someone is the way you recognize their dignity. The second is the suffering of all people. Suffering and pain are very different. To make contact, not with their pain, but with their suffering, is what is important. The third is the independence of all people. Some people lose the self-confidence needed for independent action and thought. We need to encourage independent thinking.

A big part of medicine is encouraging independent participation in medical care. And last is the dependence that we all have on one another. Most of my patients would not be worried about dying. They would be more worried about being a burden to their families and to society. We have not done the best job possible in our profession of recognizing that and bringing it to the surface for discussion.

Q: What made Dr. Frist, Sr., special?

A: Dr. Frist, Sr., had the unique capacity to really know people. He was an old-fashioned family doctor who made house calls. When we try to know people — whether it’s as a doctor, a minister or any other profession for that matter — we can discover great things and help them realize their potential.

Q: How has the patient landscape changed since you went into practice?

A: We have a much more mixed society, especially those who may be new to the country. We need to learn from people from other backgrounds that are not like our own. They can have insight into other people in our culture that we might not have.

Q: How has healthcare changed for physicians over your career?

A: It’s a much healthier environment now. When I trained, I was on call every other night for five years; that’s hard on a person and their family. I think the balance is better, but it certainly is different. When I was growing up in rural Mississippi, a doctor was part of your family. Now, it’s less so, but I think we take better care of people than we did in the sense of applying more expertise in specific areas. While I long for the old days in many ways, we’re not going to see that anymore. It was hard, but it was also extremely gratifying.

I jokingly say I’m a pediatrician for adults. Before I was a physician, I prepared to be a priest. I had always hoped to have a profession in which you could help people, but also see the spiritual dimension to their suffering.— Karl VanDevender, M.D.

Q: Would you say there’s also more of a team approach to medicine?

A: We are not doing this alone, and we’re not just doing it with our medical colleagues. We’re doing it with others with whom we work, whether it’s in information technology, in the hospital kitchen or with the housekeeper. Often they can give us insight into the suffering of our patients that we ourselves may not see. One of the big differences now is to make an effort to include everyone as part of the team.

Q: Have you seen that spirit of communal insight impact your work with the Alan Alda Center for Communicating Science (aldacenter.org)?

A: Alan and I have a partnership, and we go all over the world talking to young doctors about the culture of our profession. I asked Alan, “How do you convey to someone that you recognize their inherent dignity?” I think you recognize someone’s dignity by making your best effort to get to know them on an intimate basis. Basically, it’s teaching people the vocabulary of emotions.

Q: What advice would you offer a doctor just starting out?

A: When I was young, I studied Aristotle. He wrote to his son that happiness is living in accord with your most sacred values. Happiness is not a mink coat or a diamond ring. So, I want you to be happy.